What are Rare Earth Minerals? Why do they matter on the chessboard of geopolitics?

By Daramola Luke and Saheed Muheez

From smartphones and laptops to Electric Vehicles (EVs), fighter jets, and solar panels, modern technology powers our world, relying on 17 crucial elements known as Rare Earth Elements (REEs), which are extracted from “Rare Earth Minerals (REMs)”. The unavoidable reliance of the world on REMs for several purposes has cemented their pivotal role on the chessboard of geopolitics. Global superpowers are in the business of political manoeuvres to secure access to these critical resources. US President Donald Trump recognises the strategic importance of REMs and is pursuing a mineral resources agreement with Ukraine. Kyiv is believed to command a resource potential worth trillions in critical minerals, including REMs. While details of the proposed deal remain contentious, at its heart lies the highly valued rare earth minerals.

What are REMs?

REMs are naturally occurring mineral deposits which may contain one or more Rare Earth Elements (REEs), a group of 17 metallic elements in the periodic table. REMs possess very unique magnetic, conductive and electronic properties which makes them indispensable and critical for various purposes across a wide range of industries. Despite being called “rare”, these elements are relatively abundant in the Earth’s crust, but they are rarely found in high concentrations and are difficult to extract and refine, making their supply strategically and economically significant.

REMs are generally categorised based on their composition and the concentration of REEs they contain. They are divided into Light Rare Earth Minerals (LREMs) and High Rare Earth Minerals (HREMs). LREMs include Scandium, Lanthanum, Cerium, Praseodymium, Neodymium, Promethium, Samarium and Europium. They are commonly found and more concentrated in larger and more accessible deposits which makes them relatively easier and cheaper to mine. On the other hand, HREMs are found in smaller and more complex deposits which makes extraction difficult and expensive to run. Elements in this subset are Gadolinium, Yttrium, Terbium, Dysprosium, Holmium, Erbium, Thulium, Ytterbium and Lutetium. HREMs are more important and therefore more expensive.

Priceless status

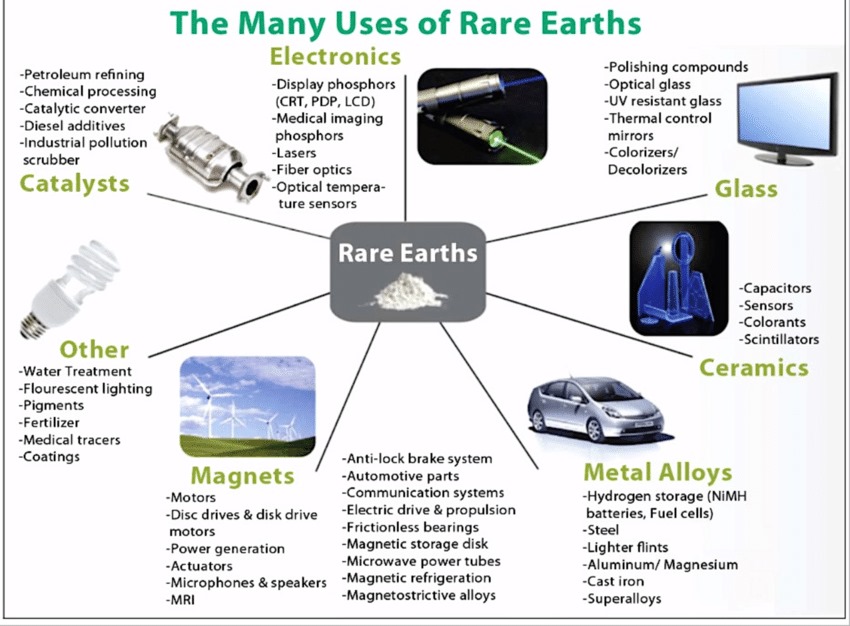

Rare Earth Minerals (REMs) are critical to numerous modern industries, particularly high-tech manufacturing, renewable energy and defence. Their unique magnetic, conductive, and luminescent properties make them indispensable for a wide range of applications. Each year, nations allocate billions of dollars to national defence and aerospace development, where REMs play a pivotal role. They are essential for military technology, including jet engines, missile guidance systems, and radar equipment. Samarium-cobalt magnets are integral to fighter jets and satellites, while Yttrium and Gadolinium contribute to stealth technology and high-temperature alloys, enhancing military capabilities and strategic defence systems.

In the electronics and consumer technology sector, REMs are integral to nearly every smartphone, laptop and tablet. Elements such as Neodymium, Terbium and Dysprosium are essential for high-performance magnets used in speakers and vibration motors, while Europium and Yttrium enhance display screen quality. Lanthanum plays a crucial role in camera lenses, improving optical performance in mobile devices. With the global push for net-zero carbon emissions and the growing demand for renewable energy, REMs are indispensable to clean energy technologies. Neodymium and Praseodymium are key components in the high-strength magnets used in wind turbines and EV motors, enabling lightweight and efficient designs. Lanthanum and Cerium contribute to hydrogen fuel cells and advanced battery technologies, enhancing sustainable energy storage solutions. In robotics, computing, and artificial intelligence, REMs such as Gallium and Indium are vital for semiconductors and quantum computing, facilitating AI development and data storage. Their role in fibre optics and superconductors makes them critical for the future of computing.

Magnetic centres

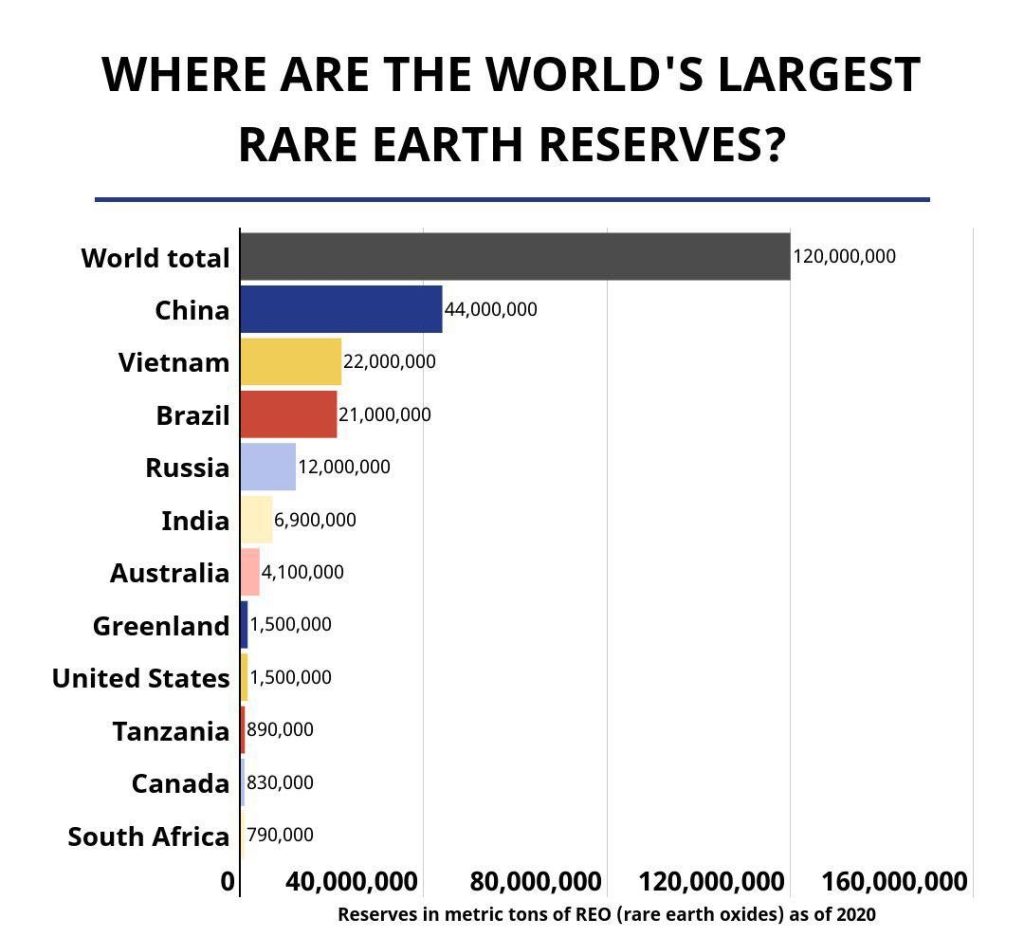

Deposits of REMs are dispersed across the Earth’s crust, but locating them in high concentrations remains a challenge. Despite this, certain countries possess commercially viable reserves. Of the 193 nations, China holds the largest known stockpile, with over 44 million metric tonnes approximately 38 per cent of global reserves. In addition to this vast resource base, Beijing leads in mining operations, accounting for 70 per cent of global extraction, and dominates processing with an overwhelming 90 per cent share. Significantly, Vietnam holds the second-largest stockpile of REMs, with 22 million metric tonnes, closely followed by Brazil with 21 million metric tonnes. In contrast, the United States and Russia possess lower reserves, at 1.5 million and 12 million metric tonnes, respectively.

Geopolitical chessplay

The stark disparity between US and Chinese reserves underscores one of the key motivations behind US President Donald Trump’s push to acquire Greenland. According to United States Geological Survey (USGS) data, Greenland holds the world’s eighth-largest REM reserves, estimated at 1.5 million metric tonnes. This move was widely interpreted as an attempt to reduce Washington’s reliance on China for REMs supply—a concern echoed by the Global South, where nations are increasingly seeking to diversify supply chains and safeguard their industrial and national interests.

President Trump also hopes to secure REMs from Ukraine as compensation for past and possible future US aid to Kyiv. Under the terms of the bilateral as seen thus far, Ukraine is expected to give up future revenue from state-owned mineral resources that include rare earth minerals as well as critical resources like graphite, lithium, titanium and uranium. For Trump, these minerals and metals are of utmost importance to the US tech power in the brewing Sino-American frictions, where Taiwan sits at the epicentre. Taipei produces over 60 per cent of the world’s semiconductors, many of which depend on REMs. In the event of heightened conflict, supply disruptions could become a tool of retaliation. China has already restricted Gallium and Germanium exports (important for semiconductor production), demonstrating its readiness to weaponise critical materials in geopolitical disputes. Beijing’s stranglehold on the production of these rare minerals and its looming trade war with Washington leaves Europe and the Global South at an arduous crossroads due to the potential halt in supply of important materials needed for industrial advancement and energy security.

In light of Russia’s protracted war with Ukraine, sustained Western sanctions have restricted Moscow’s access to high-tech components that rely on rare earth minerals, forcing it to strengthen trade ties with Iran and China. The conflict has also underscored the frequent deployment of cutting-edge military hardware from anti-aircraft defence systems to drones, all of which depend on REMs for production. Furthermore, with the proposed negotiations seeking to end the war in Eastern Europe, Ukraine is likely to lose substantial amounts of its mineral resources as a large amount of them worth $350 billion are located in Russian-occupied territories which Moscow is expected to hold on to. This further demonstrates the crucial and strategic importance of REMs in the ever-changing world of geopolitics. For state actors and corporations, unrestricted access to REMs sustains the lifeblood of modern technology, making it essential for industrial progress and national security. As the demand for REMs intensifies, the global chessboard will see more aggressive manoeuvres, and nations without control over these resources risk falling behind in the technological race.