Special Report: Despite Kwara govt’s crackdown, underage street begging persists in Ilorin

By Adeneye Islamiyah Temitope

The sun had only just begun to stretch its golden arms across the quiet streets of Ilorin. A soft breeze carried the scent of dust and roasted corn, mingling with the distant hum of traffic. At Tipper Garage, the calm of the morning was quickly broken by a familiar chorus of small voices calling out to motorists, palms outstretched, eyes filled with hope and exhaustion.

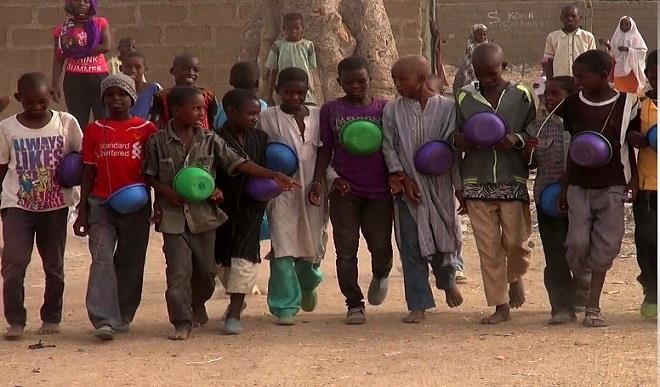

Among the swarm of tiny figures darting between vehicles were Aishat and Fati, two young girls no older than ten. Their bare feet tapped lightly against the warm tar as they moved from car to car, their voices almost lost in the noise.

Aishat clutched the edge of her worn hijab, her gaze fixed on the window of a slowing taxi when this reporter approached her. “We beg because we are hungry,” she said softly, her voice barely louder than the rumble of engines. Beside her, Fati nodded, her small hands clasped in front of her as if in silent prayer. “We would love to go back to school one day.”

But Aishat and Fati are only two faces in a crowd that stretches far beyond Tipper Garage. Across Ilorin — from the busy lanes of Tanke to the chaotic junctions of Geri Alimi — hundreds of others share the same struggle, their stories echoing the same refrain of hunger, loss and hope.

Is street begging legal?

Street begging is illegal in only a few states in Nigeria. But underage begging is banned across the country. Under the Child’s Rights Act 2003 (CRA), a child who is found begging is considered to be in need of care and protection (Section 50) and the competent authority is obliged to bring him or her before a juvenile court to determine the measures of protection required (CRA Section 50(1) (h) (i).

Moreover, the exploitation of children for hawking or begging for alms is a criminal offence punishable with up to 10 years of imprisonment (Section 30).

The CRA explicitly includes street children in the definition of “child in need of special protection measures”. A street child is defined as: (a) a child who is homeless and forced to live on the streets; in market places, and under bridges; and (b) a child who, though not homeless, is on the streets engaged in begging for alms, child labour, prostitution, and other criminal activities which are detrimental to the wellbeing of the child (Section 277(6)).

Government efforts

Earlier this year, the Kwara State Ministry of Social Development, in an effort to sanitize the state, launched several exercises, clearing dozens of beggars from the streets for profiling and possible repatriation.

According to the ministry, during one of the exercises, no fewer than 94 beggars, including 43 women and 51 men, were evacuated for profiling and possible repatriation.

The government warned that street begging would no longer be tolerated in the state.

“We’ve carried out massive sensitization through jingles to inform the public that street begging is banned in Kwara State,” said the state’s commissioner for social development.

Begging persists despite govt intervention

However, in spite of these operations, begging remains visible across the city, suggesting that enforcement by itself is not enough.

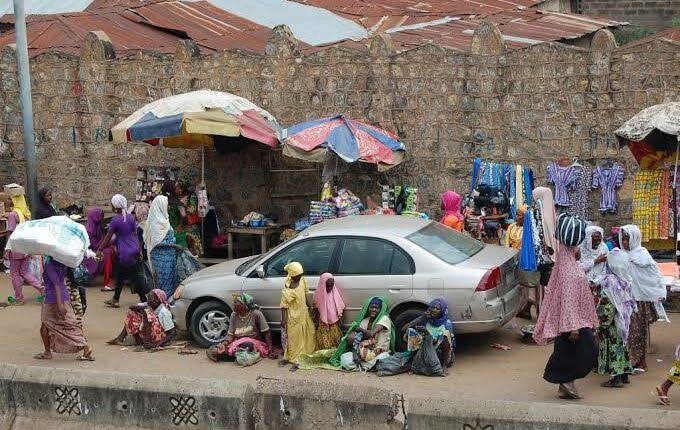

Traders at Tipper Garage described regular encounters with children and adults who beg to survive.

This reporter also observed that street beggars, most of whom are underage, also flock to other streets of Ilorin such as Gambari, Geri Alimi, Sango, and other major places in Ilorin.

A trader at Tanke, who identified herself only as Mrs. Aminah when this reporter approached her, said street beggars are still in every corner of Ilorin.

She added, “Simple interventions such as food support or small income sources would reduce the pressure that drives many to the streets.”

Why do they return back to the streets?

For Mr. Olaide Olawuwo of TRUorganic, a Non Governmental Organization, he emphasized that poverty is one of the causes of why street begging is increasing.

He added, “In 2022, we have 141,325 drop out students. Students drop out rate keeps increasing annually because of parents’ inability to provide basic needs for the children.”

A research paper established a direct link between poverty and street-begging, revealing that as poverty deepens, more people are drawn into begging to meet their daily needs.

The study further noted that while street-begging is often seen as a nuisance, it is, in truth, a symptom of systemic poverty.

Another research paper showed that more poverty is associated with more involvement in begging activity as the findings of the study revealed positive relationship between the poverty and begging activity.

The report stated, “Generally, poverty abets street-begging activity in a society. It is concluded that full-time beggars are poorer than part-time beggars nevertheless, being male or female does not justify the level or rate of poverty and suffering of the beggars. Street-begging activity has been seen as nuisance in the society but to desist from it poverty problem must be address in the society.”

Way forward

According to the study, the underlying issues — joblessness, inequality, and weak social safety nets — are addressed, the cycle is bound to continue.

He recommended that government poverty-alleviation programmes include this marginalized group and that the public shift from enabling begging on the streets to supporting sustainable interventions that prevent people from falling into it in the first place.

The paper stated, “It is recommended to the government to incorporate this socio-economically less privileged group in the Nigerian poverty alleviation programme. Likewise, public should desist from encouraging this group from engaging in begging activity by extending more their helping hands to the poor and destitute before turning to any form of beggars in the society.”

For Mr Ishola Toheeb, a student in Ilorin, he said both the government and citizens can help by providing skills and opportunities.

“They should be empowered with skills and opportunities instead of being forced to beg,” he told this reporter.

Beggars still on street because of givers: Govt

The State’s Commissioner for Social Development, Mrs. Marian Nnafatima, told this reporter that street begging is a national concern, not one peculiar to Kwara State.

“Begging is a national issue,” she said. “It is not unique to Kwara. One major challenge we face is that many well-meaning citizens keep giving money to beggars. This only encourages them to remain on the streets instead of seeking better alternatives.”

Mrs. Nnafatima explained that the ministry is working with non-governmental organizations to promote rehabilitation and education for those affected.

“In partnership with an NGO called Out of the Street and with funding support from Mafoone, we have been able to enroll about 50 child beggars back in school,” she added.